Last February, 103-year-old Hazel Simpson of Port Angeles, Washington, died. This was notable not only because of her age, but because she was the last Native speaker of Klallam, the language of the S’Klallam Tribe of the Olympic Peninsula.

The S’Klallams have worked hard over the last decade to revitalize their language, publishing a dictionary and starting a program to teach Klallam as a second language to schoolchildren on the Elwha Reservation. But something irreplaceable died along with Simpson, the last living person to learn Klallam at home and speak it as a primary language.

Like endangered species, languages are dying across the planet. By one estimate, one language vanishes every 14 days. At this rate, according to language researchers from the University of Hawaii and Eastern Michigan University, between half and 90 percent of the world’s 7,000 distinct languages will disappear by the end of the century –– a higher rate than the loss of the planet’s biodiversity. Of the 176 known languages once spoken in the U.S., 52 are thought to be dormant or extinct.

Languages die for complex reasons. But research suggests a combination of imperialism, economic development and mass urbanization, all of which tend to favor dominant national languages, such as English, Spanish, Mandarin and French. A recent study by an international group found a striking connection between economic growth and the disappearance of indigenous languages.

According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, roughly 370,000 Native-language speakers live in the United States, approximately 250,000 of them in the West. Of the roughly 70 Native languages still spoken in the region, Navajo is by far the healthiest, with more than 170,000 speakers.

Many languages, however, are down to their last speakers. Northern Paiute is one of dozens of Western tongues classified as “critically endangered.” Northern Paiute, also known as Paviotso, belongs to the Uto-Aztecan family of languages, once spoken by dozens of tribes from southern Mexico to Oregon.

Today, there are no more than five surviving native speakers of a critically endangered dialect of Paviotso, all of whom live in Bridgeport, California, on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Maziar Toosarvandani, a linguist from University of California, Santa Cruz, is working with three of these last speakers — two of them in their 90s — to build an online dictionary and a compendium of tribal stories.

Such efforts have proven invaluable. Toosarvandani points to the case of the Oklahoma-based Miami Tribe, where a scholar reconstructed the phonetics and grammar of this dormant language using 200 years of anthropological records. Today, the language is being taught to local schoolchildren through the Myaamia Center at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. “There are examples of languages that have been extremely endangered or dormant, and that have been revitalized,” Toosarvandani said. “It’s possible. But you’ve got to have the documents to do it.”

The Endangered Languages Project, an ambitious partnership between Google, the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Eastern Michigan University and First Peoples’ Cultural Council not only collects troves of information about the world’s threatened languages but plots them on an interactive online map.

These initiatives will not preserve threatened tongues. The hope, however, remains that linguistic information can be saved in a sort of time capsule, awaiting future rebirth.

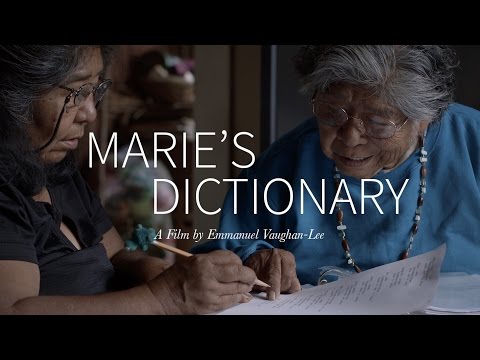

The film below tells the story of Marie Wilcox, a Native American woman who is the last fluent speaker of Wukchumni and a dictionary she created that documents the language. The Wukchumni tribe is part of the broader Yokuts tribal group native to Central California. The film was produced by Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee and the Global Oneness Project.

This article appeared in the print edition of the magazine with the headline Endangered languages.